Join us! Register here.

Join us! Register here.

Be sure to check out my e-newsletter, The Barber Brief. You can visit the website for the full archive and subscribe to have each new issue mailed directly to your email inbox.

November 5, 2021

URGENT! It has just come to my attention that at the November 10 Reno City Council meeting, under item D.2, Mayor Schieve and Reno City Councilmembers will consider accepting a recommendation to permanently change the name of N. Center Street to University Way, between the Truckee River and Ninth Street, in addition waiving the standard six-month waiting period for the change to go into effect.

Members of the Reno community have just learned that on September 23, Washoe County’s Regional Street Naming Committee, which forwarded this recommendation to the City Council, approved this request, which came directly from President Sandoval, without soliciting any input from the community at large or consulting any experts in the history of Reno, Nevada, Center Street, or its name—and that these efforts were begun back in April (and perhaps earlier) by President Sandoval with the written support of Mayor Schieve and others.

Despite that months-long involvement in this effort, Mayor Schieve’s intent to “surprise” the community with this plan was revealed just this week, when she appeared in a video called “The Next Stage of Downtown Reno” stating, “I’m looking at an initiative with the University to change one of our streets into University Avenue [sic]—I’m not going to say which one.”

A permanent renaming of one of Reno’s original streets deserves extensive community discussion, as there are far greater implications and repercussions than those related to branding, City-University partnerships, public safety, and the impact on the few businesses or other entities that happen to be located on the street in the present day. The change would constitute a permanent disruption to the continuity of a fundamental component of Reno history.

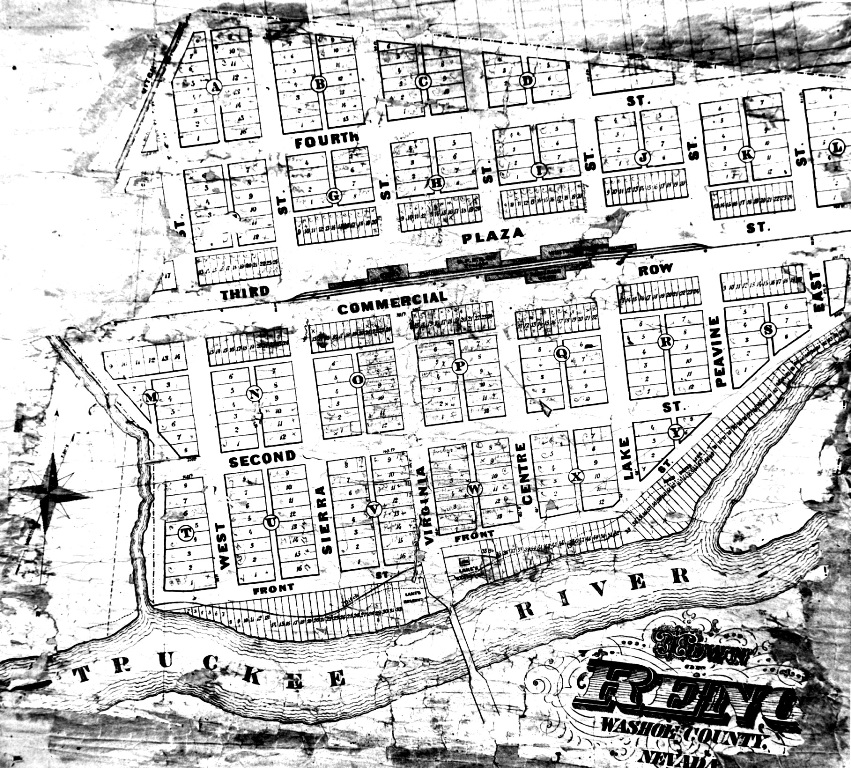

Changing the name of N. Center Street to University Way would permanently erase the name of one of Reno’s original streets, named by the Central Pacific Railroad in 1868, from the only section of street that was originally given that name. This is a distressing proposition with significant repercussions for Reno’s historical continuity and for the longstanding heritage and meaning of Center Street to Reno’s history and to local residents. It completely fails to acknowledge or respect the important role that N. Center Street plays in Reno’s history.

To pursue this name change in such a top-down, non-inclusive manner as though it is entirely justified by current strategic priorities and the historical record is neither accurate nor responsible. The fact that this measure appeared on public agendas for the Board of Regents and the Washoe County Regional Street Naming Committee does not constitute public engagement with Reno citizens or the historical community. This decision demands deliberate outreach in order to ensure that it is thorough, supported, fully vetted, and supported by Reno residents and that all potential implications and repercussions have been considered.

Please view my full letter with supporting documents and photographs below.

See below for a history of the “University Avenue” name through newspaper articles.

President Sandoval can be reached directly at president@unr.edu

Reno Mayor Hillary Schieve at mayor@reno.gov

Councilmember Neoma Jardon at jardonn@reno.gov

Councilmember Jenny Brekhus at brekhusj@reno.gov

Councilmember Devon Reese at reesed@reno.gov

Councilmember Oscar Delgado at delgadoo@reno.gov

Councilmember Bonnie Weber at weberb@reno.gov

Councilmember Naomi Duerr at duerrn@reno.gov

January 4, 2021

I was so pleasantly surprised and honored to find myself included among Reno Gazette-Journal columnist Sheila Leslie’s list of Heroes to inspire Northern Nevada in 2021 with some very kind words she wrote about me and my efforts to keep the community informed about Reno development, historic preservation, and related issues. You can read the full column at the above link.

Sheila Leslie’s column in the Reno Gazette-Journal was published online on December 23, 2020 (click on the image to link to the full piece).

I’m so grateful for the support, and encourage anyone who shares these interests to sign up for my upcoming free newsletter, The Barber Brief, where I’ll offer information, research, and analysis to promote greater citizen participation in issues related to Reno’s development. Happy New Year!

My op/ed on why certain members of Reno’s real estate development community are backing Reno City Councilmember Jenny Brekhus’ opponent, and why that should concern anyone who believes councilmembers should act in the public interest, was published by This is Reno on October 28, 2020. UPDATE: Brekhus won.